Automata Theory

Any statement in propositional logic maps to a boolean function that can be expressed in conjunctive normal form (CNF).

Consider the CNF of a full adder:

\[

\begin{array}{| c | c | c | c | c }

c_{in} & p & q & s & c_{out} \\

\hline

T & T & T & T & T & A \land B \land C \\

T & T & F & F & T & A \land B \land \overline C \\

T & F & T & F & T & A \land \overline B \land C \\

T & F & F & T & F & A \land \overline B \land \overline C \\

F & T & T & F & T & \overline A \land B \land C \\

F & T & F & T & F & \overline A \land B \land \overline C \\

F & F & T & T & F & \overline A \land \overline B \land C \\

F & F & F & F & F & \overline A \land \overline B \land \overline C \\

\end{array}

\]

\[

\quad s \equiv (A \land B \land C) \lor (A \land \overline B \land \overline C) \lor (\overline A \land B \land \overline C) \lor

(\overline A \land \overline B \land C) \quad \\

\]

\[

\quad c_{out} \equiv (A \land B \land C ) \lor (A \land B \land \overline C) \lor (A \land \overline B \land C) \lor

(\overline A \land B \land C) \quad \\

\]

The logical expression can be simplified with the laws of boolean algebra to find a more optimal expression, to then be implemented in

a digital circuit. This logic sits within the category of combinational logic: input bits are combined by a set of logical connectives to

arrive at output bits. By adding memory, we introduce the concept of the finite state machine. State means memory, transformed by

state-transitions from timestep to timestep as defined by some clock cycle. Combinational circuits have a propagation delay: a time

taken for inputs to map to stable outputs in the digital circuit. The clock cycle needs to exceed the longest

propagation delay within the state machine for the state machine to be synchronised. We can express the state machine mathematically

using a 5-tuple.

\[ M = \langle \Sigma, S, S_0, \delta, F \rangle \]

\( \quad \Sigma \) is a non-empty finite set of symbols belonging to an alphabet

\( \quad S\) is a non-empty finite set of states

\( \quad S_0\) is an initial state belonging to S

\( \quad \delta\) is a state-transition function \(\delta : S \times \Sigma \rightarrow S\)

\( \quad F\) is a set of states considered final

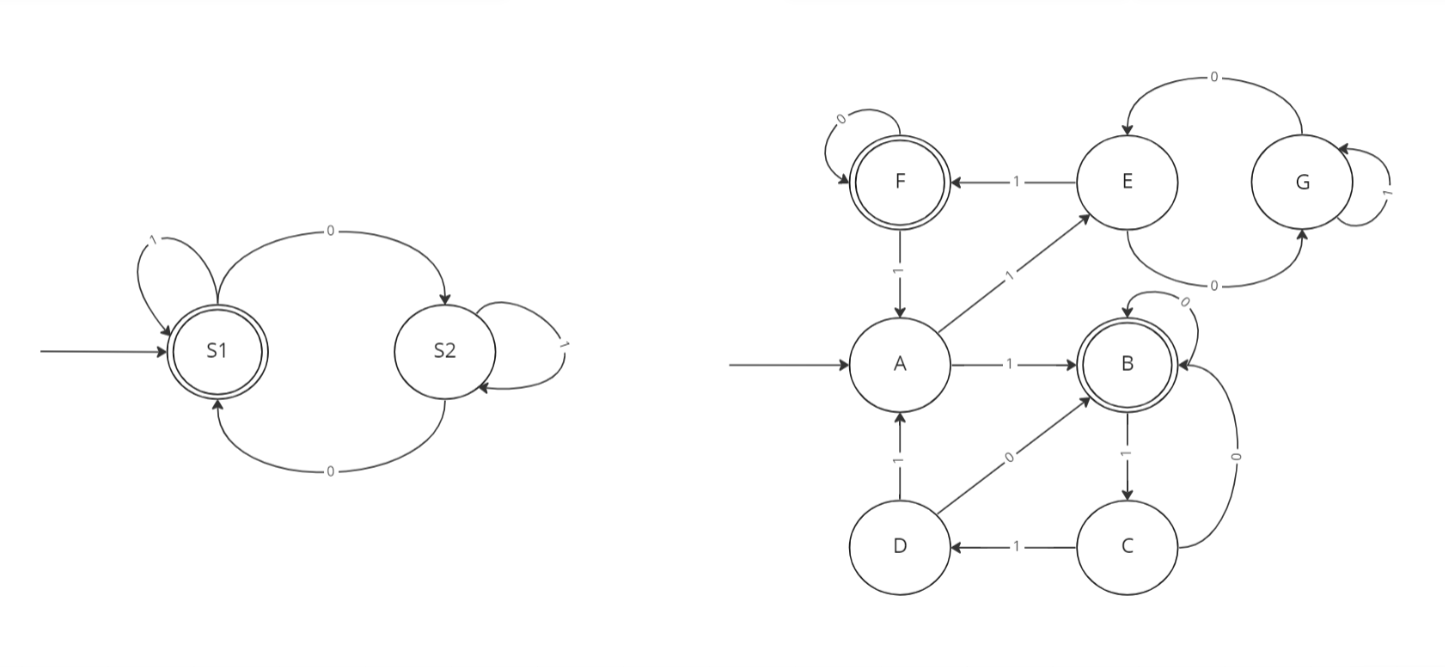

A 'run' in the finite state machine is defined as an ordered set \( q_0, q_1, \dots, q_n \) where \(q_i \in Q\) and \(q_i = \delta(q_{i-1}, a_i)\). Consider the following example state machines. The first defines the grammar of a binary alphabet that excludes all binary words with an odd number of zeros. The second defines an arbitrary grammar for a seven-character alphabet.

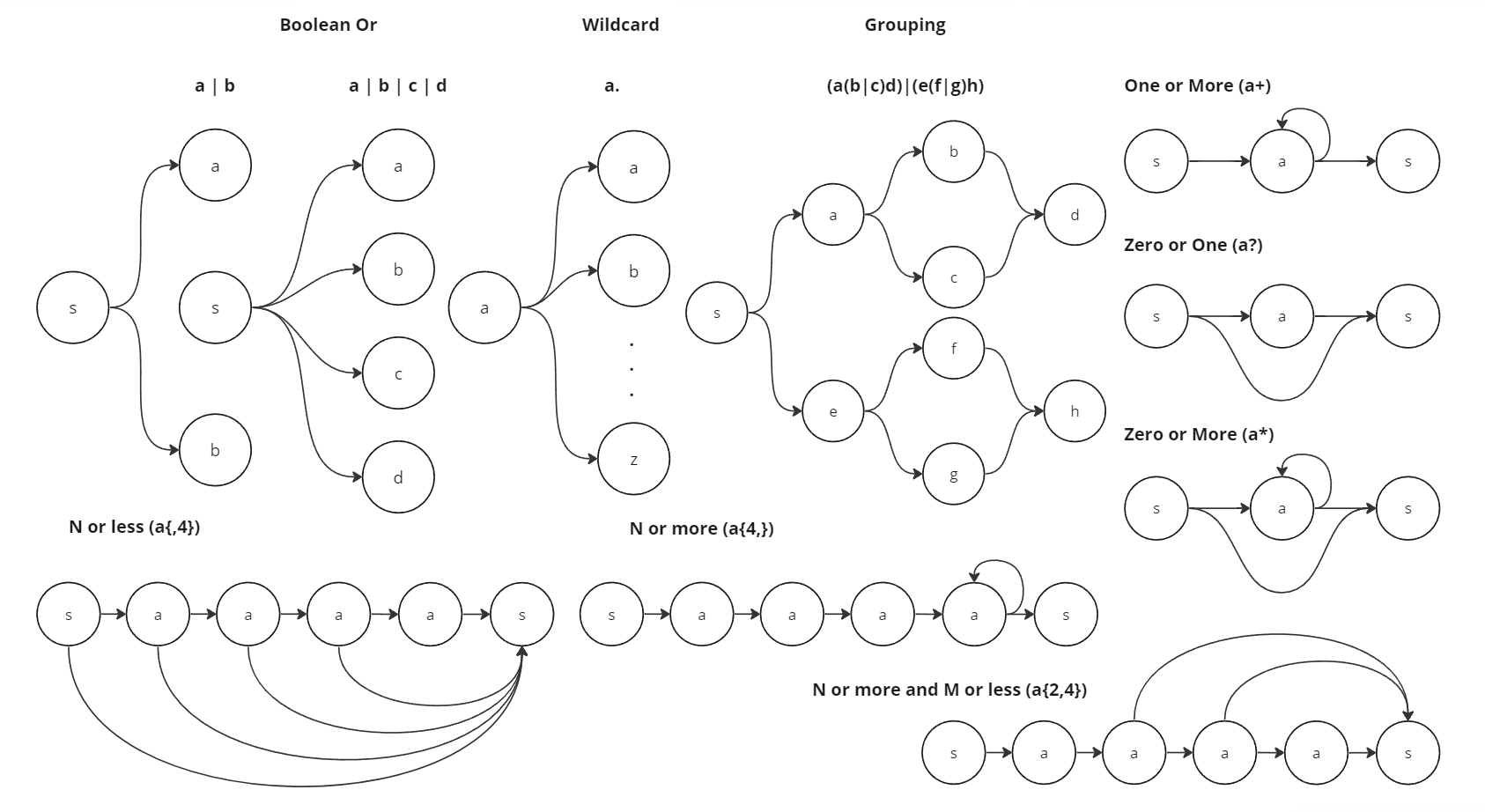

Finite state machines read and evaluate regular languages. If a given input is fed to a state machine that terminates succesfully, then that input is a grammatically valid expression in the regular language that state machine defines. A regular language is a language defined by a regular expression. A regular expression is a sequence of characters that define which strings that can be made from a character set 'match'. Regular expressions are typically constructed from the following:

- Boolean or: '|' for example "deer|dear" matches "deer" or "dear".

- Grouping: '()' for example "a(b|c)d" matches "abd" or "acd".

- Zero or one quantifier: '?' for example 'ab?' matches 'a' or "ab".

- Zero or more quantifier: '*' for example 'ab*' matches 'a', "ab", "abb", "abbb", etc. but not "abc".

- One or more quantifier: '+' for example 'ab+' matches "ab", "abb", "abbb", etc. but not 'a'.

- N matches: '{n}' for example x{4} matches "xxxx".

- N or more: '{min,}' for example x{2,} matches "xx", "xxx", "xxxx", etc.

- N or less: '{,max}' for example x{,3} matches 'x', "xx", "xxx", but not "xxxx".

- N or more and M or less: '{min,max}' so x{2,4} matches "xx" and "xxxx" but not 'x' and "xxxxx".

- Wildcard: '.' for example 'a.' matches "aa", "ab", "ac", etc.

Kleene's algorithm transforms any given nondeterministic finite automaton into a regular expression. Lets look at the state machines that express the above regex primitives.

We now know how to create a state machine to parse validate the grammar of expressions in a regular language. Evaluate of the expressions themselves is also conceptualised by a state machine, where state represents memory, state-transitions represent instructions that manipulate state, and the 'run' on the state machine is defined by a sequence of valid instructions (a program).

Pushdown automata extend state machines to formulate and evaluate context-free languages. The formal definition of a pushdown automata

extends that of the finite state machine by that of a 7-tuple.

\[ M = (Q, \Sigma, \Gamma, \delta, q_0, Z, F)\]

\( \quad Q\) is the finite set of states

\( \quad \Sigma \) is the finite input alphabet

\( \quad \Gamma\) is the finite stack alphabet

\( \quad \delta\) is the transition relation

\( \quad q_0\) is the initial state

\( \quad Z \) is the initial stack symbol

\( \quad F\) is the set of final or accepting states

A state-transition in \(M\) is denoted \((p,a,A,q, \alpha) \in \delta\) meaning that for a state \(p \in Q\) with an input \(a \in \Sigma\)

and a current topmost stack symbol \(A\), a transition will occur to state \(q\) that pops \(A\) from the stack and pushes \(\alpha\) to the

stack. The existence of the stack gives the pushdown automata a sort of primitive memory, where the next state-transition to occur can

depend on an input previously pushed to the stack. In the context of programming, the extension of state machines to pushdown automata

allows the programmer to save state when context switching to and from function calls.

Pushdown automata can be extended to linear-bounded automata which define context-sensitive languages. Linear-bounded automata

access a memory tape of finite-length that can be moved leftwards or rightwards. Thus, previous inputs can be accessed without the use

of stack operations. The movement of the memory tape is analogous to jump and branch instructions. Turing machines model

recursively-enumerable languages. A turing machine is a model of computation that consists of a memory tape divided into cells containing

symbols from a finite alphabet, a head that can move across the memory tape and read from or write to its cells, a state register storing

state, a table of instructions that given the current state and current tape symbol instructs the turing machine which symbol to write

to the current cell and how to next move the head. We can express this formally with a 7-tuple.

\[ M = (Q, \Gamma, b, \Sigma, \delta, q_0, F)\]

\( \quad Q\) is the finite set of states

\( \quad \Gamma \) is the finite tape alphabet symbols

\( \quad b \) is the blank alphabet symbol

\( \quad \Sigma \) is the set of input symbols that initialise the tape

\( \quad \delta \) is the transition function

\( \quad q_0 \) is the initial state

\( \quad F \) is the set of final or accepting states

Turing Machines describe recursively-enumerable languages. These are languages for which the subset of grammatically valid expressions in the set of all expressions formed by the language's alphabet can be enumerated with recursion. The language hierarchy thus far discussed can be further extended with Long-Short-Term-Memory neural networks and natural language processing.