Formal Language Theory

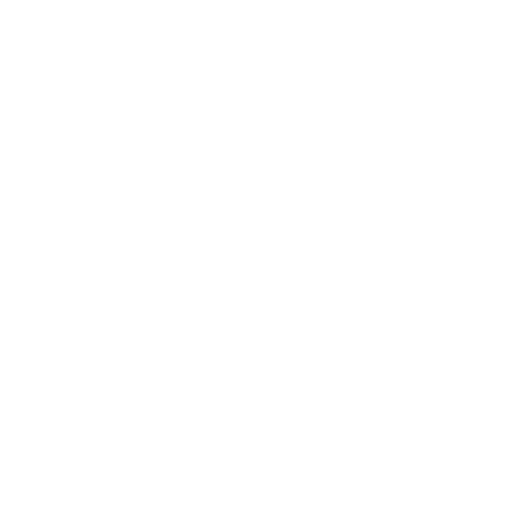

Formal Language Theory studies the structure of formal language. We start with a formal language \(L\) over an alphabet \(\Sigma\) to which some well-formed words of all words \( \Sigma^\ast \) belong. Let's consider the example of a language \(L\) over the alphabet \(\> \Sigma = \{\epsilon,0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,+\}. \>\) What is referred to as the formal grammar can be thought of as a surjective mapping from \(\Sigma^\ast\) to \(L\) such that words belonging to \( \Sigma^\ast \) that are not well-formed map to the empty word \(\epsilon\).

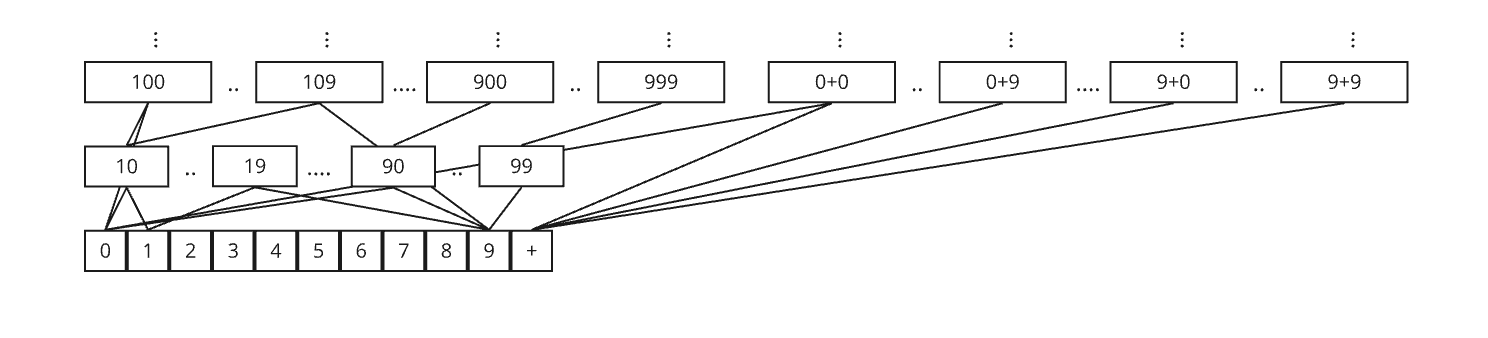

We can think of formal language as encoding of objects and relations into symbolic objects and syntactic relations. We can think of formal language theory as the recursive-equivalent: the encoding of symbolic objects and syntactic relations into symbolic objects and syntactic relations. In the above example, the diagram itself is a formal language with alphabet consisting of the symbols, nodes and edges required for its construction. We could describe this formal language with other formal languages with alphabets of equal or greater size, making for an infinite recursion, if we so desired. Because formal language theory describes formal languages using formal language, the properties of the initially described objects and relations are lost. For instance, in the above example, the diagram describes the syntactic relations of the arithmetic operator on natural number operands, but not arithmetic itself. We could imagine an additional arithmetic relation over this diagram. For instance, two relations would exist between the well-formed words \(9\) and \(9-0\): one for the construction relation, and one for the arithmetic relation.

Operations exist over formal languages themselves. Let's look at a few examples. \[ L_1 \cup L_2 = \{w \>|\> w \in L_1 \vee w \in L_2 \} \] \[ L_1 \cap L_2 = \{w \>|\> w \in L_1 \wedge w \in L_2 \} \] \[ \neg L = \{w \>|\> w \notin L \} \] \[ L_1 \cdot L_2 = \{wz \>|\> w \in L_1 \wedge z \in L_2 \} \] \[ L_1^\ast = \{ \epsilon \} \cup \{ wz \>|\> w \in L_1 \wedge z \in L_1^\ast \} \] \[ h(L_1) = \{h(w) \>|\> w \in L_1 \} \] \[ \phi(L_1) = \bigcup_{\sigma_1, \> \sigma_n \> \in \> L_1} \phi(\sigma_1) \cdot \ldots \cdot \phi(\sigma_n) \] \[ h^{-1}(L_1) = \bigcup_{w \in L_1} h^{-1}(w) \] \[ L^R = \{w^R | w \in L\} \] The closure properties of formal languages form categories of formal language. These categories include regular languages, deterministic context-free languages, context-free languages, context-sensitive language, recursive languages, and recursively-enumerable languages.