Multiprocessing

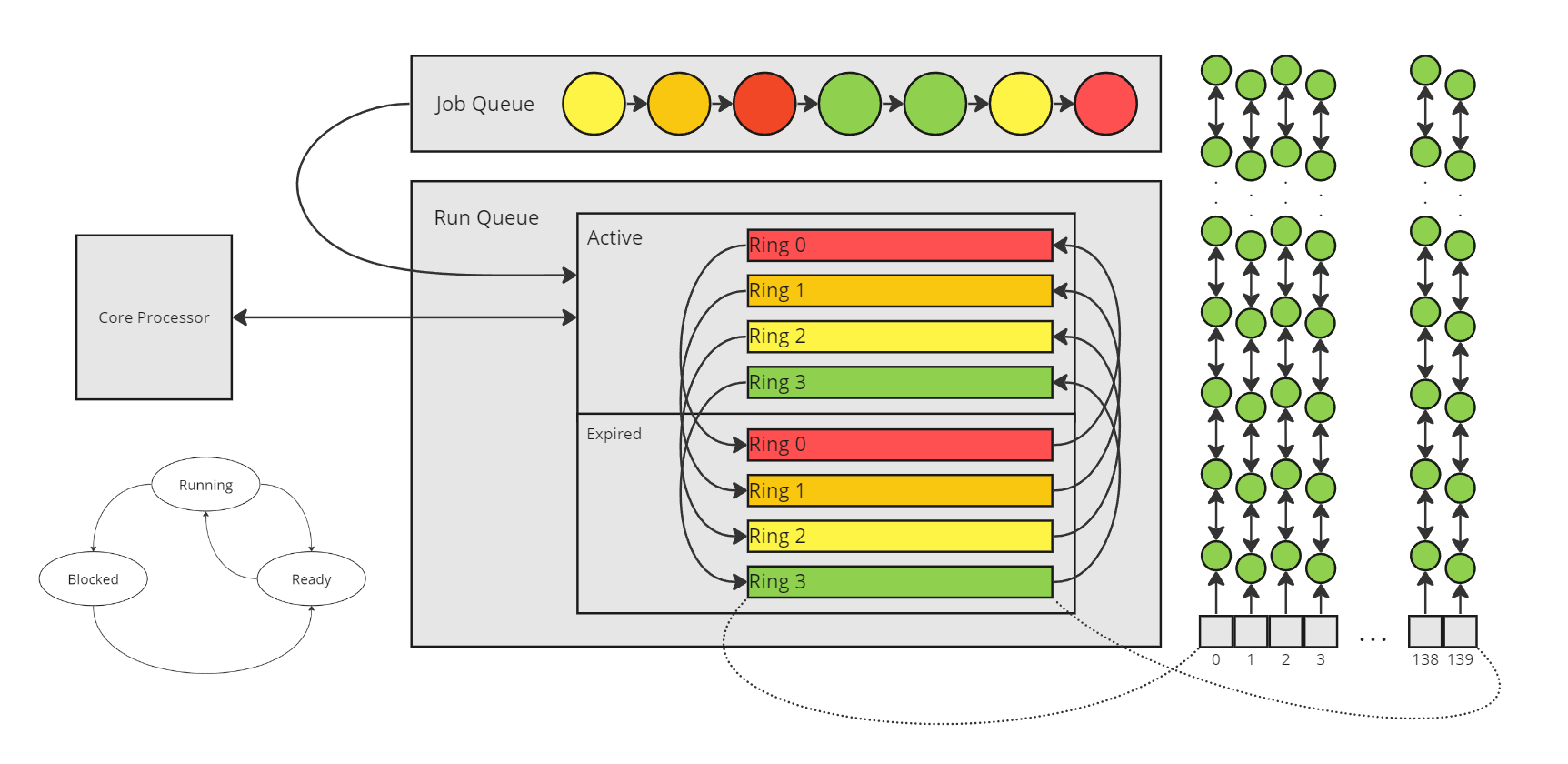

Multiprocessing is the simultaneous execution of tasks, achieved through parallelism and concurrency. Parallelism describes multiple core processors processing tasks simultaneously. Concurrency describes core processors context-switching between multiple tasks at a fast enough rate to give the impression of simultaneous execution. Each core processor can enact its own fetch-execute cycle, creating parallel threads of execution. There are typically many more tasks being run on a computer then there are cores of execution. To give the impression of simultaneous execution of these tasks, operating systems will have task schedulers to manage the context-switching action of each of these parallel threads.

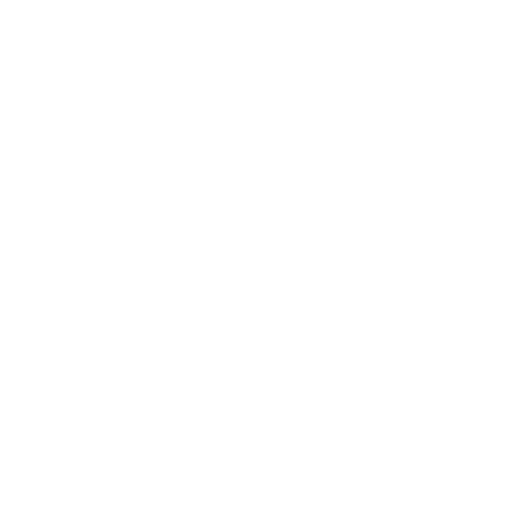

The scheduler manages a job queue, a ready queue and a device queue. These queues contain process control blocks (PCBs): data structures used by the operating system to describe processes. A process control block contains all relevant information describing a specific process. The above visualisation is an example taken from the linux kernel's 'O(1) Scheduler'. This has been replaced by the 'Completely Fair Scheduler' which removes the need for active and expired queues, and uses red-black tress in place of doubly-linked-lists for PCB storage. PCBs have a quantum (a time slice) that upon expiration moves them to the expired queue. When the active queue is empty, the queues are swapped, to continue execution of each unfinished PCB. The PCBs have a priority and niceness value. The priority value ranges from -100 (most) to 39 (least) while the niceness value ranges from -20 (most) to 19 (least). The niceness value is for user rather than kernel applications and is superimposed onto the priority value range from 0 to 39.

The bottom right DFA shows how a PCB moves between queues, from a ready state in the job queue, to a running state, to a blocked state (i.e. pending IO response) or straight back to a ready state (quantum expiry) before re-entry into the running state until task completion. Additional terms are often used, namely the long-term scheduler, the medium-term scheduler, the short-term scheduler, and the dispatcher. The long-term scheduler is responsible for managing process flow between the job queue and the run queue. The medium-term scheduler is responsible for managing process flow between the run queue and the blocked queue. The short-term scheduler is responsible for managing the execution of the most prioritised processes within the run queue. The dispatcher is additional kernel software that upon being signalled by the short-term scheduler that a PCB block requires immediate execution, initialises the runtime of the process itself.

A thread of execution is a sequence of instructions being executed by a core processor. Parallel threads of execution can be achieved with multiple core processors, each processing the runtime of a distinct process. Concurrent threads of execution can be achieved by the action of the scheduler, which can switch thread execution from process to process at a fast enough rate to give the impression of simultaneous execution. The scheduler can also manage intraprocess as well as interprocess concurrent threads. If a scheduler preempts a running process into a waiting state and waiting process into a running state, the thread of the previously running will save its current context to its stack, CPU registers included, to avoid data loss. Similarly, concurrent threads executing within a singular process each have their own call stack, and perform the same state-save when preempted to become temporarily dormant. Thus, concurrent threads share all process resources (instruction memory, data memory, heap, file descriptors, child processes, etc) except the call stack, of which they each have their own.

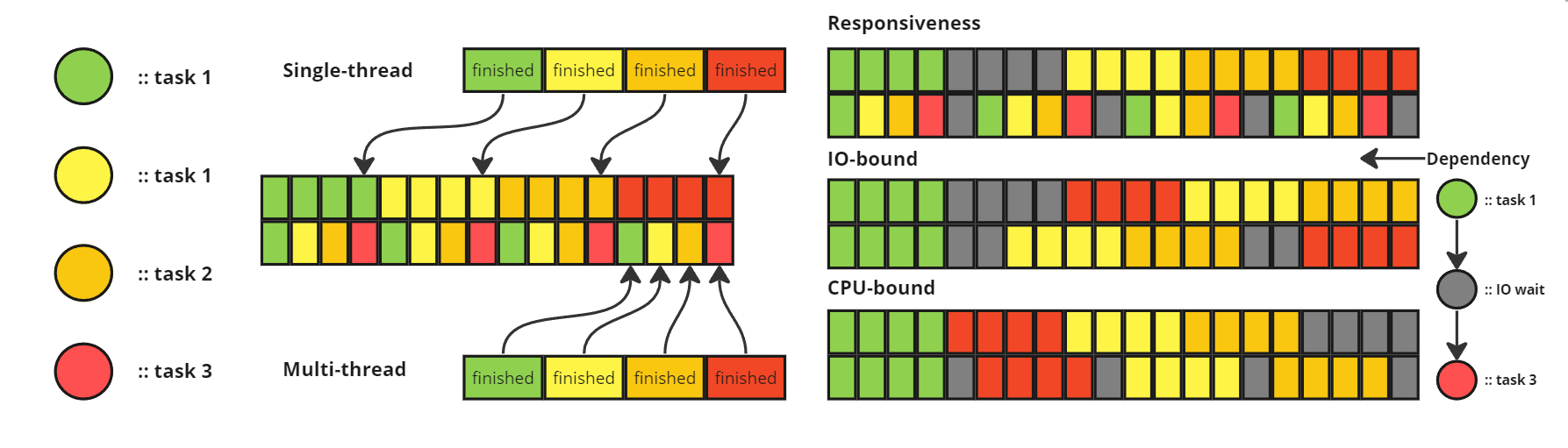

Whether a sequence of independent tasks is processed sequentially or concurrently it will have the same total execution time. Concurrent threading does however assist with the responsiveness of applications. For example, making an edit request to a shared presentation on an online multithreaded workspace will ensure that the edit request is processed in the same batch as other user requests within a given time period, rather than as a queue. Concurrent threading can also ensure that IO-bound processes can advance the execution of a number of tasks while waiting for a response for a specific task. Note that an IO-bound process is a process with IO-bursts substantially larger than CPU-bursts, meaning its performance is bounded by IO performance. CPU-bound processes can also benefit from multithreading, by allowing smaller tasks to run amidst much larger tasks. For instance a simple status signaller subtask that runs alongside a computationally expensive scientific simulation.

Returning now to a previous point, each thread of execution within a process shares all resources save for the call stack, of which each has its own. This fact creates the complication of criticial sections and race conditions. Criticial sections are areas of memory that can be accessed by multiple threads of execution. Implementation details of the scheduler are left to the OS, thus the concurrent execution of threads is unpredictable from the process's point of view. Race conditions emerge from this unpredictability, from the fact that the stored values in a critical section may differ depending on whether thread A or thread B access it first. Thus, it is necessary for the process to be developed in such a way that critical sections are safe-guarded by some sort of synchronization primitive. A synchronization primitive is an abstract data type (a set of primitive data structures wrapped in well-defined access methods) offered by the OS to perform exactly this.